In order to reach the studio where G Perico made his scorching full-length debut album All Blue, it’s necessary to navigate the Los Angeles hills with the kind of driving skill set that only a stunt driver might possess. Studio City is fairly homey on the ground level, but the deeper you head into the hills, weaving through stucco mansions behind large, almost Draconian gates, the more you notice what an escape the high elevation offers. When I finally stopped, it wasn’t at the house itself, but to my Lyft driver telling me to hike the rest of the way up. This, was a far cry from South Central, Los Angeles, where the temperature is always set to survival. Studio City is a whole different world — even the people feel different. There’s a mild enjoyment to just being here, relaxation and ease.

Perico hand-picked this place and this studio just for that reason. It serves as a means to get away from his South Broadway studio, the one he refers to as a place where too many of the homies would be around to clutter things up. It’s the studio where a gold plaque for E-40’s “Choices,” — the record Perico co-produced with Poly Boy — hangs right outside, next to a slew of other plaques for a German producer who helped out Milli Vanilli deceive Grammy voters in 1990. “I asked him, ‘Did ya’ll know they weren’t really singing?” Perico says, imitating the producer and his loose German accent. “‘Everybody knew,’ he said.”

Inside the studio, there’s a blue rag draped over the microphone, a manicured stretch of speakers, a large keyboard, controller and iMac sitting on a desk. On a nearby shelf, books such as The Secret by Rhonda Byrne and Success Through Stillness by Chris Morrow and Russell Simmons stick out, brought in by friends. Stepping outside to the foyer, there’s a mattress on the ground, a slew of alcohol bottles from whiskey to vodka behind it, and tables set up for lounging. It’s clear there was recently a party here.

Perico’s manager Pun, a large man with a rounded face dressed in all black — right down to the black and white Dodgers hat — has a hand in plenty of Los Angeles’ rap scene, from the production group League of Starz to Sage the Gemini. Their relationship is that of big brother and little brother; Pun roping Perico in after one of his infamous house parties when Perico crashed his car after having too much fun. I remark that G’s the hottest young rapper in LA at the moment and both of them flash wide grins. “Say that then! Say that then!” they both say. Consider it said.

“Kendrick kicked the LA wave off,” Perico reminds us. “ScHoolboy about to drop. Kamaiyah about to drop. Mozzy about to drop … sh*t it’s about to be lit.”

PHILIP COSORES

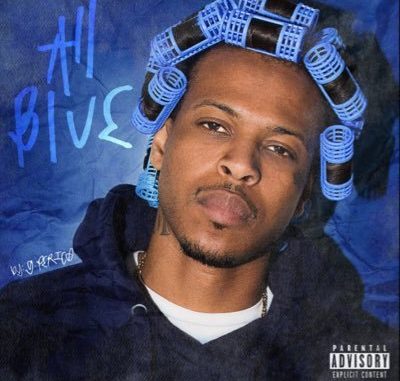

All Blue, G Perico’s follow-up to 2016’s Sh*t Don’t Stop is a condensed ride through South Central, Los Angeles. It’s autobiographical, thickly outlined with personal touches like the tattoos that adorn Perico’s body. All his ink is a form of allegiance to himself and the Broadway Gangster Crip set that he claims, they all serve as easy reminders of West Coast slang and a hustler’s mentality.

A “2 UP” tattoo adorns his right hand, a BG sits at the top of his left cheek, right underneath his eye. It’s clear on sight that G Perico’s DNA is layered within LA hip-hop, his curls are an immediate indicator of that, though he loathes being roped in with G-Funk. He raps with the same unflinching pimp joy that swells around Too Short records, a yelp reminiscent of DJ Quik and a posture of invincibility that make him sound and feel like it’s his divine right to carry the torch for tough-guy LA rap.

“I got a story to tell,” he says with a relaxed tone inside the studio. “I can articulate a lot and even if it’s not someone’s story, they can admit I’m a cold motherf*cker.”

As an ‘80s baby who grew up during the end of the peak crack era Los Angeles, the rapper, born Jeremy Nash has seen it all. Plenty of his friends have died or been sent to prison; some are facing indictments, others are still holding onto those same blocks and corners Perico used to pivot and work like he was Kyrie Irving running point. “Real f*cked up sh*t,” he says of his backstory. “I didn’t have no sad story because I was going to go out there and get it.”

Earlier this month, he performed at The Roxy, delivering his All Blue material for the first time as a headliner. TF & Cuz Lightyear, two emerging acts in their own right proudly set the stage for Perico’s blue crowning moment. The stage is hallowed ground for him; a box-like cathedral for other acts of his ilk who’ve touched that stage and then leapt into other areas.

It’s also the scene of a memorable performance in 2016 where he took the stage only hours after getting shot. “It’s something about that stage, something about that motherf*cker that make me get buck,” he says. “No other place does that for me. But me getting shot? Me getting shot made me angry. The reaction from everybody, starting from Sh*t Don’t Stop to now made me wanna go harder.” He recalls going on stage and performing a verse acapella, to an audience that was more polite than rabid rap crowd. “Like it was some poetry sh*t,” he laughs. “My leg was all wet [with blood, from his earlier wound] but I still finished that show.”

Stories of survival permeate All Blue, the Priority Records release that Perico released at the end of April 2017. Cutting through all the street-talk and prophesying is the revelation of how Perico is a survivor — right down to wicked deeds done out of necessity. He’ll rap about growing up and jumping off the porch in South Central in the same breath as describing how he sold crack to his uncle, then warn that walking with your back towards traffic in his neighborhood is like asking for a near death experience. His turbulent life is vividly strung out over the course of thirteen tracks on the album’s brief 35-minute runtime. When it comes to his own criminal record record, he jokingly saying it’s not extensive but “not normal” skimming through some juvenile hall and city jail stints. “I’ve done a little dumb sh*t, I got a track record.”

PHILIP COSORES

One of All Blue‘s best tracks, “Get My Staccs,” is a real-life motto to him, a song about various episodes in his life with women and more. Then there’s the “How You Feel” video, where he articulates every situation he’s been arrested, told through the lens of someone snitching on him and cops running into his So Way Out clothing store on South Broadway. Perico is a natural pessimist, but through the outpouring of positive responses to Sh*t Don’t Stop and All Blue, the icy feel of wanting to quit and start over began to dissipate.

After all, the OGs of Los Angeles have recognized him; Snoop Dogg has taken a liking to him, telling him he need come by the studio so he can “put that final spray on that curl.” According to Perico, DJ Quik has embraced his sound, and one the young rapper’s primary producers, Rare Beats, who hails from Watts, introduced Perico to Nipsey Hussle when he got serious about pursuing rap full-time. For Perico, it’s beginning to set in that the music industry offers him something totally different, a vast change of pace from low-level street hustling.

He’s heard all the jokes about his curl and he laughs it off. Why? Because he didn’t even think about a “look” to bring people in visually, he thought of being himself. The curl he has now has been standard since 2012, a second attempt after he got maced in jail. A long curl has been a wish of his for a while. Now it’s reality.

“I’m one of the only people that’s doing something,” he says in reference to his friends. “I had to stop making myself accessible. Cause I would take an Uber or park my car at the studio and somebody would always be at that f*cking door with their negative energy, their problems… so, when you’re growing and getting all the way serious about this sh*t, you gotta think like a business. This is a job, now.”

He continued, “A homie hit me up and I told him I felt bad for not coming down to the hood. Cause that was my routine: Get dressed, jet on down to the block. Now I get up, and I say, ‘F*ck, I gotta go rap.’ People started believing in it. I got with Pun and I started noticing, it could help people. Me thinking on a gangster-ignorant sh*t, me getting fast money would only help people for a limited period of time. I been through the process so many times, getting a lot and then falling off and having to start over. That sh*t felt like insanity. I felt like I had to step out my comfort zone in order to get it.”

On 111th and San Pedro, Perico found some of his inspiration. He’d flip as a kid in friend’s backyards, taking in the blue hair rollers in the hair of OG Crip members. “You remember how the OGs were swole, muscle-bound n*ggas. Didn’t matter if you were Blood, Crip, everybody was big. Everybody would hop out in khaki suits, riding in Lowriders and Suburbans. I actually got the idea from Bad, my homie Sinbad. He was like the leader of the hood, head of the hood. That n***a knew how to flip, fight, have b*tches. He was one of my biggest influences, like he was my pops. Lot of my sh*t comes from him. Only the Eastside used to know about it. A lot of my upbringing, I feel like that’s the duty of a lot of artists to bring where they’re from to the world.”

PHILIP COSORES

But whatever else crops up G Perico, South Broadway will always be his first love. It embraced him and he couldn’t do anything wrong. He was royalty there and he was enamored by the uncut gangsters who roamed the neighborhood. It’s where he encountered haters for the first time, “ghetto hate” he calls it. The freedom he had as a kid, the availability to pursue the spoils of hustling? Someone would be lurching over him, annoyed by it all. “Jealousy,” he sums it up. “When I pull up and do sh*t for the hood, it’s a lot of motherf*ckers who wish they could do that. You can’t hate on me out in the open, you gotta hate blocks away and never hate in my face.”

When his attention focuses on something, Perico lingers a bit before picking up momentum. He could riff on The Great Migration of black families heading North and West (“everybody gotta a little South in them”) or how the Ku Klux Klan has roots in the Los Angeles Police Department; his worldview isn’t limited to one particular border or box. The mainstream facets of gang culture in regards to language and slang? “A catch-22,” he says. “Cause people have died over that sh*t.”

Perico’s thought processes zoom through all possible outcomes, before settling naturally on Occam’s Razor, the simplest solution is the correct one. That’s why after studying other successful artists, All Blue clocks in at its brief yet confident run-time. “You’re gonna eventually go up against your idols,” he says. “Of course I wanna be one of the best so I study people’s projects and I noticed — all the best projects are short. I plan on releasing a few more short projects. If I drop few long ones, 18-22 songs and people only like four of them motherf*ckers, people don’t wanna hear that. It’s a thin line. I wanna keep them entertained. I plan on doing this sh*t for decades.”

He knows that LA means more to hip-hop than anyone would let on. It’s all he knows. Which explains the curl, the staunch support of fellow acts from the area and more. “I just feel like when I do sh*t, I shouldn’t be apologetic about what I’m doing or to fit in. I’m LA. And LA is important to the country and it’s important to the whole culture of f*cking rap. I feel like I’m the Bible for the LA sh*t. This is Los Angeles. This is the type of sh*t that goes on in Los Angeles and this is how the majority of the people live.”

As far as signing to a label is concerned, he’s far more comfortable working with Priority and distribution. “All the labels is going to do is tell you to go get a hot record,” he says flatly. “They may give you some nice money but that’s about it. I still don’t have the intentions to take a deal yet because I want to get the demand higher to get what I truly want. Had I signed last year? That would have been the death of my growth. So when I do partner with a label, I don’t want no questions. I just want to steamroll on everything.”

He pauses for a moment to take a phone call. A friend of his is outside with a gift. As soon as the man walks inside, he’s holding on to a pair of Nikes. Perico and Pun’s eyes light up. The white and blue Cortez have gold coins painted into the Nike check. Without hesitating, Perico kicks off the all blue Nikes he already has on his feet and slips on the Cortez.

Leave a Reply